3 Haziran 2025

A Lasting Solution Demands Justice and Fairness For All Cypriots But who is usurping whom?

Human rights are not selective. They belong to every individual regardless of ethnicity, religion or political affiliation. Justice and fairness need to apply to all Cypriots equally.

Yet, the lived experience of Turkish Cypriots in the past 61 years calls this principle into question. In property rights, political equality, and international engagement, Turkish Cypriots often find themselves held to different standards.

So we need to be clear about what “usurping”, a word which is echoed in so many conversations at the moment, means to Turkish Cypriots.

Who usurped the Republic of Cyprus?

The Republic of Cyprus was founded in 1960 as a bicommunal partnership between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. However, in 1963, the Greek Cypriot leadership proposed illegal constitutional changes and when Turkish Cypriots rejected these, violent clashes followed, and they were forced out of state institutions and the government itself.

In March 1964, the UN will have been perfectly aware of two things. First, that both Greek and Turkish communities were two equal founder members of the Republic, and that the Turkish Cypriots were by far the main victims of the conflict with 25,000 displaced Turkish Cypriots alongside just 250 Greek Cypriots. Yet, the UN resolution 186 was agreed without the consent of the Turkish Cypriot community, and it quite arbitrarily referred to the Greek-Cypriot-only assembly as the legitimate government of Cyprus.

From a Turkish Cypriot perspective, this is a fundamental “usurpation” – a unilateral claim to a state that was never designed to belong to just one community. The Greek-Cypriot-only republic continues to use this status to this day to punish Turkish Cypriots and their foreign business partners at will.

Who rejected peace and was rewarded nevertheless?

In 2004, the UN Annan Plan offered a blueprint for a power sharing governance model under a bizonal, bicommunal federation. Turkish Cypriots voted overwhelmingly in favour while the Greek Cypriot side rejected it by an even larger margin. Yet, the Greek Cypriot Administration (GCA) was still admitted to the EU days later, while Turkish Cypriots remained isolated.

This reinforced the idea that cooperation by Turkish Cypriots brings no benefit, while obstruction by the Greek Cypriot side carries no consequence.

Who is being prosecuted, and who is protected?

For 51 years, no property developers or estate agents in the north were prosecuted by the GCA, despite large-scale building on formerly Greek Cypriot land. This inaction reflected a tacit understanding that both sides had a practical need to house displaced people and make use of abandoned properties.

Given the protracted nature of decades of talks without a result, it was inevitable that each side would want to make further improvements to their lives through housing, tourism, transport and trade which required building on land which belonged to people on the “other side”. In any case, new building did not alter the title deeds ownership of the land, and in many cases increased the value of such land for its owners.

There are numerous government and commercial properties built on Turkish Cypriot owned land in the South which benefit Greek Cypriots. Larnaca Airport, for instance, partially built on such land, was acquired by the GCA without the consent of the owners. The compensation payment was a trivial amount and not payable until the Cyprus problem is solved.

Now, decades later, prosecutions have suddenly begun in the South of building contractors and estate agencies in the North on the basis that Greek Cypriot land is being “usurped”. Foreign nationals, including ordinary people such as a hairdresser and a retired beautician who advertised properties in the North on social media are receiving preposterous sentences.

Yet, there is no similar accountability for Greek Cypriot developers or officials who have profited from the “usurpation” of Turkish Cypriot land. In addition to the state “usurped” land for Larnaca airport, we know that some civil servants have bought Turkish Cypriot land cheaply and sold it for millions of euros. The GCA has admitted this is illegal, even within their own legal parameters based on Guardian laws, but has chosen not to prosecute.

Such selective enforcement of the law is not only morally indefensible. It also constitutes an unlawful abuse of power and erodes trust in both current and future legal systems.

Who waits forever for justice?

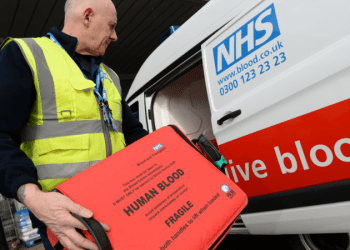

Greek Cypriots have access to the Immovable Property Commission (IPC) in the north, where they can receive compensation or restitution. Funding this budget is difficult, but over half a billion euros has already been paid out to date.

There is no IPC for Turkish Cypriots. Turkish Cypriots with land in the south are told to wait until the Cyprus problem is resolved for any compensation. One example is Mr Esat Mustafa, who fled his village in 1964. His requests for compensation and restitution of his property were constantly denied by the GCA. Even after applying to the ECHR, legal amendments and procedural barriers blocked his claim. His decades-long quest for justice remains unresolved.

How can one community be entitled to receive compensation now, while the other is told to wait indefinitely?

Where do we go from here?

The above actions do not reflect reconciliation, but punishment. Yet there is a constructive way forward. Turkish Cypriots have repeatedly supported compromise, most notably in 2004.

Both the federation based model proposed by the Greek Cypriot side and the two state model proposed by Turkish Cypriot side require bizonality – two discrete geographic areas, one for each community.

That being the case, 7% of the Cyprus landmass in the North, (the difference between the 36% currently inhabited by Turkish Cypriots, and the previously agreed 29% as per the Annan Plan) could be transferred to the Greek Cypriot community. Simultaneously, both sides could agree to “legalise” long-suspended property deeds on their side through a mass administrative transfer.

This would reflect ownerships where current generations live now, rather than the homes of people who lived 51-61 years ago, many of whom have passed away, and avoid new mass displacements. This would be completely within the ECHR judgements, notably the

Demopulos ruling which allows for exchange and compensation.

If we all agree on the importance of trust between communities and that human rights belong to everyone, then they must be shown it in law, in policy, and in everyday practice. To achieve lasting peace on the island, the moral lens of fairness must be applied to all sides equally. The opposite will surely lead to discord, stalemate and strife, once again.

ENFIELD

ENFIELD HACKNEY

HACKNEY HARINGEY

HARINGEY ISLINGTON

ISLINGTON